Let’s assume for the sake of argument that some blockchain token, either pre-launch or post-launch, is held to be or represent a security. What next? I am often asked this question by clients and others. Frustratingly, the answer is that no one really knows.

The history to date is not very illuminating. The SEC’s early settlements with 2017-style ICO issuers—such as Paragon Coin and Airfox—required the issuer to register the tokens as equity securities under Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act and undertake a rescission in offer; in theory, this could allow the tokens held by those who do not accept the rescission offer to keep trading and the issuer to get into compliance as an SEC reporting company, albeit with dramatically more limited trading venue possibilities for the token (since non-securities exchanges will not be able to list it now that it is known to be a security). However, in more recent settlements (Unikrn, Shipchain) the SEC has required that the issuer “disable” all tokens within the issuer’s control and broadly notify digital asset trading platforms that the token should be delisted—in effect, the SEC has not offered any compliance path for these projects and has forcefully shut them down. In the Telegram case, a U.S. federal court similarly enjoined all issuance of the tokens to the public. Regardless of which remedy (registration or shut-down) was selected, we presume that in all the aforementioned cases, unlike cases such as Kik/KIN and Block.one/EOS, the SEC staff or the court felt that, at the time of the settlement or court order, the token remained a security or remained integral to a securities scheme.

This leads to two questions: Is a draconian remedy like a total shutdown really what we should all expect every time a token is held to be or represent a security? Or, if there is no forceful shutdown, what does a compliance path for such a token look like? The answer to the second question depends on the classification of the relevant security.

Under U.S. federal securities law, for practical purposes, every security must be shoehorned into one of two categories: debt security or equity security. The SEC has rejected at least one attempt to classify tokens as being “investment contracts” that are neither debt securities nor equity securities—with good reason, because many of the rules essentially presume that every security is one or the other. But whether the security is classified as equity or debt makes a big difference—for example, widely dispersed equity securities can trigger the obligation of an issuer to register as a reporting company under Section 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act (a highly onerous requirement that only very mature and successful companies are able to handle (think about what Facebook, Uber, Palantir and others looked like by the time they IPO’d)). By contrast, if the token is merely a debt security, less onerous compliance paths could be available (e.g., registering the securities under the Trust Indenture Act, which has less extensive periodic reporting requirements). Additionally, if the token is a debt security, then it could trade more freely after a Regulation A+ offering—a path pursued by Blockstack for its Stacks token.

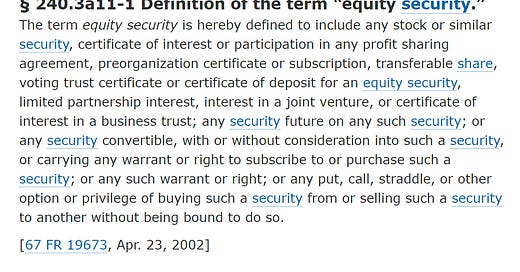

Here is how the SEC defines “equity security” for purposes of Section 12(g):

Also, for Section 12 purposes, the SEC defines “debt securities” as “any securities that are not equity securities…” Thus, if a security is not an equity security, it is automatically a debt security—even if it has few or none of the typical features of “debt”.

WIthout further ado, here is my quick-and-dirty personal cheat sheet for whether tokens that happen to be deemed securities should be classified as equity securities or debt securities. (NOTE: I am not saying the tokens are securities, just trying to figure out what kind of securities they would be if they were securities.) Of course, there is no guarantee that this analysis is correct, as there is no legal precedent or usable SEC guidance on this issue:

2017 ICO-style utility tokens

DEBT SECURITIES (token has no voting rights or powers, no rights or powers for obtaining distribution of additional tokens, token is styled as having utility to gain access to something or receive discounts on purchases of products, etc.)

(NOTE, THOUGH, THAT SEC HAS HISTORICALLY TREATED THEM AS EQUITY SECURITIES, ALBEIT WITHOUT EXPLANATION OR GUIDANCE—SEE ABOVE)

primary layer-1 tokens on PoW networks

DEBT SECURITIES (token has little or no debt-like or equity-like features, thus defaults to “debt security” if it is a security at all)

primary layer-1 tokens on PoS networks, no governance/voting

DEBT SECURITIES (in my opinion, the rewards from staking should not be likened to equity-like dividends because they differ among holders depending on the staking arrangements selected by the holders and, sometimes, the holders’ own skill in setting up a validation client etc.)

primary layer-1 tokens on PoS networks, with governance/voting

UNCERTAIN, SLIGHTLY LEAN EQUITY SECURITIES (in addition to being able to earn more tokens by staking (often ‘delegated staking’, they have the right/power to govern protocol upgrades and sometimes an on-chain treasury intended for development…thus, they may overlap with the “governance token” category immediately below)

governance tokens

LEAN EQUITY SECURITIES (have voting rights/powers, govern use of a pool of funds or parameters for minting additional tokens—unlike in PoS, any additional tokens received are less likely to be earned from a separate of skilled work like setting up validating nodes and more likely to be earned from shareholder-like functions such as voting or from unskilled staking that merely places capital into a smart contract, with any skill (or lack thereof) being supplied by the smart contract developer and not the staker)

classic TheDAO-style tokens

EQUITY SECURITIES (I assume the reasoning is self-evident - TheDAO was essentially a venture capital fund on Ethereum)

In passing, I’ll note another possible argument that goes a bit like this:

“Equity securities” are intended to represent contractual rights to voting, distributions, etc., By contrast, essentially all cryptonative tokens represent only powers to vote, receive distributions, etc., not rights to the foregoing. This is evident from the fact that such tokens are not governed by a certificate of incorporation, voting agreement or similar document conferring such rights. Even if there were such a document, it is not necessarily the issuer or any other specific party that one would want to enforce such rights against—rather, in order to exercise the putative rights of governance token holders, cooperation might be required from “core devs,” miners and many others in order to give any such rights enforceable effect. Instead of having rights, all token holders have, at best, powers—i.e., they collectively have the power to make certain smart contracts do certain things. Based on this reasoning, one would conclude that all such tokens, when they are securities, are debt securities, if for no other reason than that (ex hypothesi) they are not equity securities.

Personally, I am skeptical that this rights/powers distinction will end up trumping otherwise strong analogies to traditional equity securities, but one never knows.

As we can see, the classification of any tokens that are deemed to be securities would run across a spectrum. In theory, tokens nearer to the “equity” end of the spectrum would face tougher compliance paths (heavier SEC reporting, more trading restrictions) and tokens nearer to the “debt” end of the spectrum would face less tough compliance paths (lighter SEC reporting, fewer trading restrictions). In practice, however, the issues are quite unclear, because the SEC has not provided a target compliance paths for tokens and recently seems to evince the belief that compliance is impossible so “disabling the tokens” and shuttering the issuer is the reasonable option when a token is found to be a security after it’s already circulating. As should now be obvious, the situation created by the SEC’s reticence to provide a compliance path for tokens that are deemed to be or represent securities is far from ideal, and, as most vividly indicated by the recent price plunge of XRP after the SEC sued Ripple, adversely affects the very investors the SEC is supposed to protect. Here’s hoping to a better tomorrow and more guidance under the new administration—we shall see!

Note: Apologies for the long hiatus & thanks to those who stuck it out. I am trying to convert everyone who subscribed for a while into a lifetime free sub, but it appears to be a purely manual process so is taking a while. If you subscribed for a while & are seeing this, feel free to un-sub and DM me with your email and I will switch you to a lifetime sub.

Since I do not have much time to write these days (I have been burning the midnight oil on transactional work pretty much non-stop since November 2020), I think I will try this new format—trying to turn small things I had to write anyway (e.g. in peer discussions or notes) into rapid-fire posts that don’t take much time or energy but might be useful to people. We’ll see how it goes.

Maybe read it the wrong way, but why Reg A+ allows more freely debt trading? It is for both equity&debt securities