Defining Real and Fake DAOs

a DAO by any other name would smell as schweet?

TLDR

“DAO” in its purest form refers to an unincorporated association of persons (an ‘organization’) utilizing censorship-resistant technologies to permissionlessly (‘autonomously’) engage in non-hierarchical, widely distributed (‘decentralized’) governance of shared resources and goals.

Organizations that do not meet this definition must not be deemed “DAOs”. Thus an organization can fail to be worthy of the “DAO” honorific for many reasons—for example, because the organization is centralized (e.g., a board-managed Delaware corporation), because it requires governmental permissions (e.g., a member-managed Delaware LLC) or because it is easily censored (e.g., a Telegram chat group). I further explain the essence of DAOness below.

The Problem: “DAO” Has Lost all Clear Meaning

The term “DAO” is applied to so many different organizations that it has become close to meaningless.

I aim to correct this.

Minimum Criteria

I humbly submit that, whatever DAOs are, they must fall under three clear and distinct concepts:

be decentralized

be autonomous

be organizations

My inner autism screeches out that each of the three words— “decentralized”, “autonomous” and “organization” must be there for a reason, with none of them being redundant with the others.

Thus, “decentralized” cannot have the same meaning as “autonomous”—otherwise we would call these either “DOs” (decentralized orgs) or “AOs” (“autonomous orgs”).

We don’t call them that—we call them “DAOs”. Which means that in evaluating whether something is a “DAO”, we must separately check each of these three boxes in order to conclude that, yes, this thing is a “DAO” and not something else.

“Organization”

Webster’s most relevant definition of “organization” is as follows:

“Association” in turn is defined in relevant part as follows:

“Society” in turn is defined in relevant part as follows:

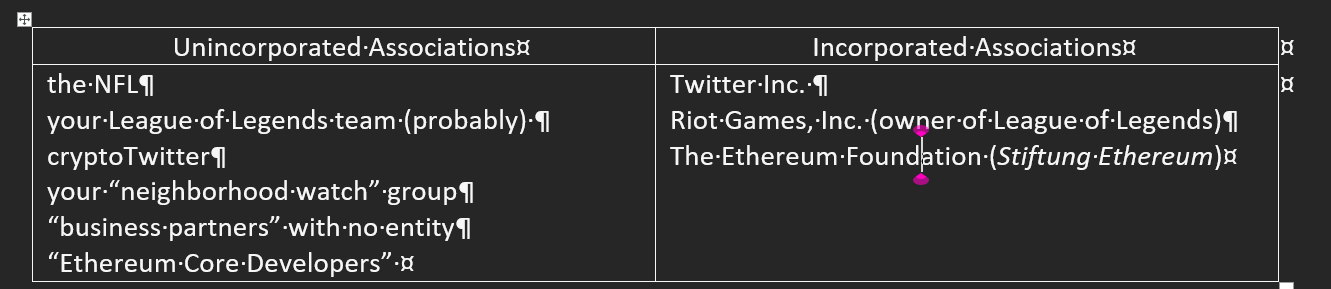

So, an organization is some sort of association of individuals for common ends or who interact with one another in a patterned way. For those who have studied corporate law, we know associations are of two main types: unincorporated and incorporated.

Basically, we all know what an “organization” is—it’s an incorporated or unincorporated association of persons. I say “persons” advisedly, since associations can also be legal persons—thus, it is possible to have an association of associations or an association of associations and individuals.

I take it as non-controversial that organizations can be centralized or decentralized, autonomous or non-autonomous. For example, Twitter Inc. is centralized (it has a board of directors as its ultimate decision-making authority) and relatively non-autonomous (it exists to generate profits for the benefit of its stockholders, who can appoint and remove the board of directors at will). The Ethereum Foundation, like Twitter Inc., is centralized (it has a board of directors or similar governing body), but, unlike Twitter Inc., is relatively autonomous (it only obeys its charter, which can be amended by its governing body—the governing body is not elected by some other authority or group of beneficiaries)*.

*Note: neither of these entities is “autonomous” in the stricter sense I believe should be used for “DAOs,” as further explained below.

“Decentralized”

‘Decentralized’ is a little harder to define than ‘organization,’ but not by much. Webster’s defines “decentralization” in relevant part as follows:

Essentially, this means that decentralization occurs when power is widely dispersed or distributed.

This could occur in many different ways: For example, all organizational decisions could be determined by tokenholder voting, but token ownership and voting turnout could be widely dispersed among many “minnows” (persons each holding a small % of total token supply/total voting power). Alternatively, different types of decisions could be delegated to different groups of persons and the coordination among these groups could be non-formalistic and non-hierarchical.

A good example of the latter type of decentralization is Bitcoin. Other than the consensus protocol itself, there are no formal governance rules existing among mining nodes, non-mining nodes, users, exchanges and core developers, but these groups all have different kinds of influence over Bitcoin and essentially govern Bitcoin on an emergent basis by “rough social consensus”. The interplay of the checks and balances these different constituencies exert on one another decide power conflicts among them and determine the fate of “Bitcoin” as an epiphenomenon. (If you doubt this and believe something different—e.g., that Bitcoin is “governed by miners”—just look into the tortured history of the ‘block size wars’ and how they were resolved.)

“Autonomous”

‘Autonomous’ is the hardest to define and is the most overlooked element of what constitutes a “DAO”. Webster’s defines “autonomous” in relevant part as follows:

Many people, I believe, misunderstand and mis-define the term “autonomous,” and it relates to a similar misunderstanding of “smart contract”.

A popular misunderstanding of smart contract technology is that smart contracts work “automatically” without human intervention—that they are some sort of “non-human agents” which engage in “algorithmic governance” of organizations. On the contrary, smart contracts are just passive object code stored on the blockchain. This code is called by miners/validators when users request it to be called by offering to pay the miners/validators for making such calls and writing their results to a new block. In other words, smart contracts never do anything unless one of their functions is specifically and manually called by a human (or the agent of a human—e.g., a “bot”). Smart contracts are the farthest thing from automatic or autonomous—they are slaves to external input.

Thus, a misunderstanding of the word “autonomous” within the term “DAO” would interpret “autonomous organization” to mean “an organization that makes use of smart contracts”. This misunderstanding is a massive ‘cheat’ which lets many arrangements that are not “autonomous” in Webster’s sense nevertheless be deemed “DAOs” merely because they involve the supposedly “automatic” technology of smart contracts. However, “autonomous” does not mean “automatic” and, even if it did, smart contracts are not automatic. Smart contracts also obviously are not autonomous because they are unconscious and inert, not spontaneous and self-controlled.

Instead of the term “autonomous” as used within the term “DAO” referring to a type of technology (smart contracts), the term “autonomous” as used in the term “DAO” refers to a type of organization. In other words, the words “decentralized” and “autonomous” in “DAO” are adjectives. The noun being modified by these adjectives is “organization.” Thus, a “DAO” is an organization that is decentralized and autonomous.

Remember how we said above that “organization” means “an association of persons”? This means that “autonomy” cannot be a quality of smart contracts—it must be a quality of the people—the organization—which uses the smart contracts.

So, then, what does “autonomous” really mean? Well, Webster’s has it quite right:

having the right or power of self-government

undertaken or carried on without outside control

(capable of) existing independently

This definition clearly reveals the role of “censorship-resistant technologies” or “dissident technologies” as a sine qua non of “autonomy” and therefore of “DAOs”. For example:

a Facebook group, a Telegram chat group, a Slack workspace, a Discord server, etc. are not “autonomous” (and therefore cannot be DAOs) because the corporations which own these platforms can shut the group down, add and remove members from the group, or alter, add or remove the group’s content at any time with little-to-no-resistance;

a group of Google employees researching and developing artificial intelligence for Google as part of their employment relationship are not “autonomous” (and therefore cannot be DAOs), because Google automatically acquires ownership of all of the ensuing intellectual property under invention assignment agreements each of them has signed, controls all of the funding for the group and has noncompetition agreements with each of the members of the group—it can remove and replace members at will, or dissolve the group at will, or defund the group at will, and it can even require that they never use any of their artificial intelligence related ideas again; and

a neighborhood watch group is not “autonomous” (and therefore cannot be a DAO) because it is only authorized to watch for problems and report them to the police/government, not to engage in its own policing and adjudication of misconduct, and if its members overstep this limitation, the police and government will deem them criminals and censor their vigilante activities.

Importantly, all of the above examples are associations of persons (and thus are organizations) and are (or at least can be) decentralized (for example, by having no hierarchy and having a one-person, one-vote decisionmaking system). But they are still not DAOs. This is because they are not autonomous; the technologies, methods of association and resources they depend on are subject to too much arbitrary extrinsic control which makes these groups “depend on the kindness of strangers”.

In contrast, any of the following could more credibly be considered autonomous and thus potentially could be a DAO:

a chat group run on the open-source, federated Matrix protocol;

the Bitcoin core or Ethereum core development communities;

a sci-fi sex cult living on a yacht floating in international waters; or

a dark web market run on Tor.

Good past, present and/or fictional examples of autonomous organizations are Hassan i Sabbah’s Order of Assassins, The Pirate Bay, Wikileaks, Bitcoin, Anonymous, Jonestown, The Interzone, Dune’s Fremen, pre-Sokovia-Accords Avengers, and the fictional F. Society from Mr. Robot. Needless to say, nation-states are also autonomous (especially superpowers).

Ironically, the original “theDAO” was not very autonomous. The way the Ethereum hardfork changed theDAO’s results of operations shows that theDAO was extrinsically censorable by a relatively small group of influential Ethereum developers and miners.* However, DAOs on Ethereum today are more autonomous than the original “theDAO” because coordination difficulty and costliness of contentious Ethereum hardforks is much higher than in 2016.

Similarly, many supposed “DAOs” that “use smart contracts” are not “autonomous”. A five-of-seven Gnosis multisig is indeed a smart contract, but an organization that is managed by such a smart contract can hardly be considered “autonomous”. Smart contracts are tools—whether they increase or decrease autonomy depends on their features and how they are used.

*Note: I am not saying that the 2016 hardfork constituted censorship of theDAO. The fact that a hardfork occurred to change theDAO’s state logic, using powers extrinsic to theDAO tokenholders’ voting powers and theDAO’s state change engine, merely shows that theDAO was more censorABLE (and therefore less autonomous) than initially portrayed.

Conclusion

Stop using the word “DAO” to refer to organizations (like Wyoming limited liability companies) that are barely even trying to be autonomous. Although decentralization and autonomy are continuums, the term “DAO” should be reserved for organizations that are close to being as relatively decentralized and relatively autonomous as possible along the dimensions that matter within the limits of current technology, and that at least aspire to become as decentralized and autonomous as possible in as many dimensions as possible by pushing the envelope of dissident technologies.

Using blockchain or smart contracts in some superficial way is not enough for an organization to be considered a “DAO”. For organizations that use smart contracts but aren’t DAOs, I prefer the term “cybernetically enhanced organizations”—cybOrgs, perhaps. Consider using that term or other similar terms instead of diluting and polluting the “DAO” concept beyond all meaning just to build hype.

Now let’s build better DAOs. = )

Post-Publication Notes

I have written another article focusing on similar issues, but targeted more particularly on distinguishing “autonomy” from “decentralization. You can find it here.

Dan Larimer’s article, “DAC Revisited” hits on similar issues and expresses similar views:

This post was *so* overdue. Thank you for the clarifications. Everyone in 'crypto' should read this.

thanks ser 🙌🏻

have been thinking that pro-DAO law reform generally gets this mixed up. Much of the time it focuses on taking an assumed end result (basically a Wyoming-type DAO) and working backwards to that. My preference would instead be to ask questions like “is there any reason why a person ought not to be able to choose to contract with a [true] DAO?” “Is there any reason why participants in a [true] DAO ought not have their personal assets protected from any creditor of the DAO?” “Is it possible and desirable for those things to be recognised and protected, while preserving anonymity?”.

Answers to those questions might end up being policy-led but at least preserve the meaning of a DAO, rather than inserting a Discord group into a hedge fund structure.