INTRODUCTION

The aim of this framework is to provide a brief, functional overview of the different DeFi ecosystem functions performed by various persons and how they might be regulated. Clarity on all the different ‘DeFi functions’ is crucial as a starting point for constructive discussion of potential “DeFi regulations”. Personally, I am opposed to all DeFi regulations other than notice & disclosure regimes for key major players. Nevertheless, it is all our interests to have a common understanding and vocabulary when discussing potential DeFi regulations.

THE FRAMEWORK

DeFi Users

“DeFi Users” are fairly self-explanatory—they are the end-users of DeFi smart contract systems. They may be token traders, token liquidity providers, token borrowers, token lenders, or users of consumer apps with DeFi functions (e.g., the player of a GameFi gaming app).

Certain regulations could potentially apply to DeFi Users—for example, liquidity providers might be seen as securities broker-dealers if their liquidity providing forms part of a regular business and the tokens they are providing liquidity for are deemed to be securities or an integral part of a securities transaction scheme.

DeFi Devs

DeFi smart contract developers (“DeFi Devs”) are software engineers who design & write “smart contracts”—i.e., software code that is designed to be stored on a blockchain and executed by miners/validators in the computing environment of the peer-to-peer network for that blockchain. DeFi Devs may also engineer ancillary software such as DeFi liquidation bots. DeFi Devs may be organized in business entities or may free-associate. The software code written by DeFi Devs is typically free-open-source-licensed, or at least source-available, and lacks a model of traditional proprietary software monetization (e.g., selling licenses).

There are two main potential vectors for regulating DeFi Devs:

DeFi Devs could be required to abide by specific regulations covering the design and creation of smart contracts—e.g., a law that imposes specific audit, testing, or design requirements on DeFi-related smart contracts. However, no such laws currently exist, and if created such laws would likely face serious first amendment challenges.

DeFi devs’ intellectual property rights relating to smart contracts could be regulated somehow—e.g., through laws imposing limitations on how smart contract code may be licensed. In effect, smart contract licenses could be treated under their own special product liability / product safety regime or, like cryptography in the 1990s, subject to special “export” controls or other sanctions.

DeFi Deployers

DeFi smart contract deployers (“DeFi Deployers”) utilize their rights as licensees or copyright holders of smart contract code to “deploy” the smart contract to a blockchain—i.e., they cast[1] a transaction to the blockchain network together with an offer to pay a transaction fee to blockchain miners/validators who create a block which stores a copy of that smart contract on that blockchain. As a result of this deployment, the smart contract is available to be run by miners/validators as a service and to have its results of operation recorded to the blockchain by miners/validators.

There are two main potential vectors for regulating DeFi Deployers:

DeFi Deployers could have tort liability for hazardous smart contracts they deploy (which could be similar to tort liability individuals already face for creating “attractive nuisances” or other hazardous conditions). This would be a post hoc liability allocation regime rather than a proper “regulatory” regime, but, like regulations, would affect ex ante incentives as well.

DeFi Deployers could be subject to specific regulations expressly regulating the activity of deploying smart contracts to blockchains—for example, making it a crime to deploy smart contracts which can be used to evade sanctions controls or may be used to trade regulated assets outside of regulated trading venues. It is important to realize, however, that such laws would be quite novel–they would essentially seek to regulate a specific type of broadcasting—i.e., the broadcasting of a smart contract deployment request to the miners/validators on a blockchain network. If smart contract deployment constitutes speech, such regulations might be subject to free speech challenges. Furthermore, as a regulation relating to broadcasting, such laws could most naturally fall under the mandate of the FCC rather than under the purview of a traditional financial regulator like the SEC or CFTC.

DeFi Miners

Miners/validators individually or collectively (depending on consensus design) perform the following activities. To the extent the above activities undertaken by a given miner/validator relate to DeFi, we may call such a miner/validator a “DeFi Miners”.

propose blocks for addition to the blockchain;

accept or endorse proposed blocks for addition to the blockchain;

receive and store broadcasted and/or private requests for including certain data or state changes in the blockchain;

choose which among the transaction requests received by them to include in the blocks they propose (and sometimes the order in which those requests will be processed within the block);

execute smart contract code (for example, calling a certain function with certain parameters on a smart contract) in order to be able to include the results of that computation in a block they propose;

‘enforce the protocol’ in performing the above actions (i.e., perform them in accordance with the protocol rules)

receive block rewards from the protocol and/or transaction fees from requesters for having their proposed blocks successfully added to the blockchain.

DeFi Miners are not traditional intermediaries or fiduciaries, but are the DeFi world’s closest analogue thereto. It would be only a minor simplification to say that DeFi Miners, like brokers or money services businesses, “effectuate transactions on behalf of others” as a for-profit business. DeFi Miners also run smart contract computations as part of their service, and thus in a certain sense are the true operational “licensees” (users) of most smart contracts. Individually, DeFi Miners have significant power to engage in arbitrary transaction reordering, and engage in or facilitate front-running or other manipulation (see MEV literature). Collectively (i.e., with a sufficient majority of block production power), DeFi Miners have the power to censor specific transactions or users or to halt, rewrite or otherwise impair the blockchain or its execution environment.

As the most powerful and essential DeFi ecosystem participants, DeFi Miners are the Coasean “least cost avoider” for bearing the burdens of “DeFi regulation.” Such potential regulations would likely extend, or share many similarities with, TradFi regulations pertaining to broker-dealers, money service businesses, securities/futures exchanges and similar intermediaries. It is unlikely such regulations would be limited by first amendment principles, since most DeFi Miners are running a for-profit businesses rather than engaging in their own free speech.

On the other hand, blockchain designs already anticipate and seek to limit the potential capture of the mining functioning by nefarious actors or the governmental authorities of any particular nation-state. Blockchain design achieves this by making the block production process expensive, incentivizing decentralization and enabling pseudonymity. This likely means that DeFi Miners would adapt to regulations by moving their operations to friendly jurisdictions and potentially limiting their “counterparties” on the p2p blockchain network to those who are known to be in friendly jurisdictions. For example, DeFi Miners might refuse to accept transaction requests from U.S.-based DeFi Relayers (discussed immediately below).

DeFi Relayers

“DeFi Relayers” transmit DeFi-related transaction requests to DeFi Miners on behalf of others. This includes any nodes in the blockchain network which generally propagate transaction requests for inclusion in the “mempool”, whether or not such nodes are also mining nodes. DeFi Relayers are often commercial “nodes-as-service” which receive & transmit DeFi-related requests from crypto wallets to DeFi Miners—for example, Infura is a major DeFi Relayer on Ethereum. Some DeFi Relayers are in the business of relaying (e.g. Infura), while others may perform relaying auxiliary to some other business (e.g., a CEX might run a relayer to facilitate withdrawals). Some DeFi Relayers are run by mere hobbyists. The relaying may involve narrowcasting, broadcasting, or a mix of the two.

DeFi Relayers, when performing the relaying as part of a business on behalf of customers, are essentially commercial service providers. This commercial service could be regulated in various ways—for example, DeFi Relayers could be viewed as similar to broker/dealers or money services businesses and thus required to register with a government agency, KYC their users and monitor, block and report on suspicious transactions. Free speech protections are not strongly implicated in the business of relaying because the DeFi Relayer is transmitting messages on behalf of others, not itself–furthermore, users always have the option of running their own nodes rather than utilizing DeFi Relayers, and thus would retain their free speech rights even if DeFi Relayers were regulated. On the other hand, DeFi Relayers who are not relaying as part of a business—as may be the case with hobbyist nodes or nodes used primarily in connection with a different business—might again have first amendment defenses or otherwise fail to be a logical target of regulation.

DeFi Function Packagers

“DeFi Function Packagers” are applications designed to help users generate a broadcastable DeFi-related transaction request message from a set of inputs describing the DeFi transaction the user may wish to perform. The transaction message may then be broadcast by the user to a DeFi Relayer or DeFi Miner through a DeFi Wallet.

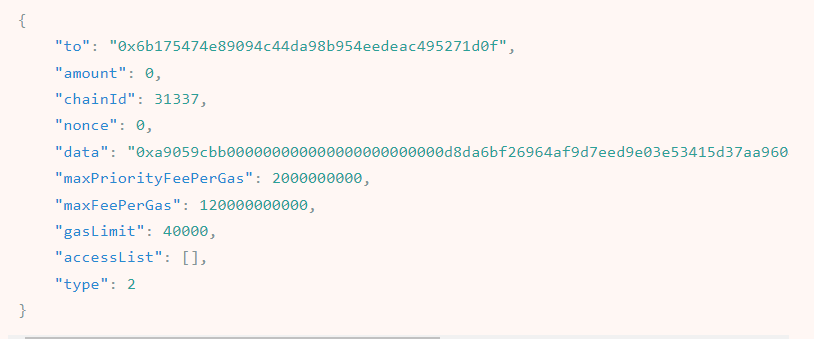

Most “DeFi websites” or “DeFi front ends” are DeFi Function Packagers. They present information about the state of the blockchain relating to a specific set of DeFi smart contracts and the capabilities of those smart contracts, and provide users an intuitive GUI to indicate what actions the user would like to perform through the smart contract. The DeFi Function Packager takes this high-level GUI input and translates it into lower-level function calls. This “function package” is bundled into a data object that can be fed into a separate DeFi Wallet application and, if the user so wishes, transmitted by the DeFi Wallet through DeFi Relayers to DeFi Miners for execution. Importantly, the DeFi Function Packager does not itself perform a relaying role or mining role, but merely translates the user’s intentions into hypothetical function calls within hypothetical mining requests. Here is what the output of a DeFi Function Packager might look like:

(source: https://www.notonlyowner.com/learn/what-happens-when-you-send-one-dai)

Applications that we think of as “developer tools” (such as Brownie, Truffle and Hardhat), as “block explorers” (such as Etherscan) and as “wallets” (such as Metamask) may also have DeFi Function Packagers.

DeFi Function Packagers are similar to many other types of software tools that abstract away some details to make software easier to interact with. In theory, they could be subject to a specific product liability or product regulation regime, but this does not have analogues within TradFi and would set a new precedent. Such regulations may also present first amendment concerns to the extent that DeFi Function Packagers may be seen as merely providing information about how to interact with software.

DeFi Browsers

“DeFi Browsers” enable users to view blockchain data relating to DeFi in a convenient format. Most “DeFi websites” combine a DeFi Browser with a DeFi Function Packager. Block explorers such as Etherscan may also be seen as more general-purpose blockchain browsers that therefore also constitute DeFi Browsers. Some “wallet applications” also include DeFi Browser features.

DeFi Browsers are similar to any other type of web browser or network browser. In theory, they could be subject to a specific product liability regulatory regime, but this does not have analogues in TradFi regulation today. Even ‘stock market browsers’ such as Bloomberg Terminal are not subject to a specific financial regulatory regime in the TradFi world–they are just tools, not intermediaries.

DeFi Advisors

“DeFi Advisors” provide advice on how a given goal should be achieved or transaction performed using DeFi. Advice can be tailored through a personal service or can be “robo-advice” rendered algorithmically—either way, it is still an advisory service. Examples of DeFi Advisors include Metamask’s “swap” service (recommends best DeFi protocol or combination of DeFi protocols to use to achieve a desired swap) and Uniswap’s “routing” service (recommends whether to use Uniswap v2 or Uniswap v3 to achieve a desired swap).

DeFi Advisors could be regulated in a manner similar to traditional securities or other financial advisors, with adjustments suitable for DeFi.

DeFi Brokers

“DeFi Brokers” are persons who take custody of digital assets for the purpose of using them or managing them within DeFi on a discretionary or semi-discretionary basis on behalf of the depositor or for the depositor’s benefit. Examples include Celsius, Voyager and (with respect to their staking services) Coinbase, Kraken and other CEXs. Certain hedge funds are also DeFi Brokers.

DeFi Brokers could be regulated in a manner similar to traditional securities or commodities brokers, with adjustments suitable for DeFi.

DeFi Investors

“DeFi Investors” invest money, effort or both to acquire ownership of tokens that capture all or part of the value of one or more DeFi systems. “Governance tokens” are currently the most popular investment vehicle for DeFi Investors. We include in the category of DeFi Investors not only venture capitalists or open-market token purchasers, but also DeFi Devs who built into the smart contract a tokenized method of capturing value and allocated some of those tokens to themselves.

DeFi Investors may be involved in an “investment contract scheme” and subject to the securities laws. Alternatively, DeFi Investors may be governing a smart contract system in a kind of open partnership that is not regulated by the securities laws and could be subject to regulations relating the liability of partners in such an enterprise.

DeFi Governors

“DeFi Governors” participate in formal governance of DeFi smart contract systems or DeFi infrastructure. This often occurs through governance tokens, and thus DeFi Governors are also often DeFi Investors. Alternatively, DeFi Governors may be non-investors who received delegations of voting power from DeFi Investors.

DeFi Governors may have tort liability or other kinds of liability for the results of their governance decisions. FATF has suggested that DeFi Governors may become subject to regulation as virtual asset service providers (VASPs)/money services businesses, depending on their level of power over the relevant DeFi system and the relevant properties of the DeFi system.

DeFi Promoters

“DeFi Promoters” publicly market, promote and publicize the availability and usefulness of DeFi. They may be subject to liability under existing consumer advertising regulations (FTC) or consumer financial protections (CFPB). To whatever extent DeFi may entail regulated financial products, then DeFi Promoters may also be liable for their promotional activities under existing financial regulations (e.g., securities “touting” rules). Alternatively, new laws could be passed specifically regulating DeFi Promoters. Because of free speech protections, any such DeFI marketing laws would likely only cover DeFi Promoters who are engaged in marketing as a business, rather than those who are merely expressing their opinions and enthusiasm for a given DeFi system.

Combined Roles & Suggested Regulatory Focus

Most DeFi Participants do not strictly limit themselves to a single ‘DeFi function,’ but rather undertake multiple functions, some of which are synergistic. For example:

The best monetization strategy for a typical “crypto wallet” application would likely involve having the application be a DeFi Browser, DeFi Function Packager and DeFi Advisor all rolled into one.

A DeFi “front-end” is not really “user-friendly” unless it combines both a DeFi Browser and DeFi Function Packager. Some DeFi “front-ends” are also DeFi Advisors (for example, because they provide a routing recommendation engine).

A single centralized service may wish to be both a DeFi Broker and DeFi Advisor in order to cater to multiple types of clients.

Many DeFi “teams” combine DeFi Developers, DeFi Deployers, DeFi Governors and DeFi Investors.

An open question would be whether regulations that might be inappropriate or infeasible for a given specific function by itself do become appropriate or feasible when a certain mix of functions is being fulfilled by a single person or group. Specific combinations of functions–such as a single person or group running a DeFi Browser, DeFi Relayer, DeFi Miner, and DeFi Advisor as an integrated whole–may raise significant conflicts of interest that warrant proactive regulation.

We suggest that initial regulatory discussions focus on centralized functions–such as DeFi Brokers–and persons or groups that vertically integrate many DeFi functions in a manner creating systemic risks or conflicts of interest. A benevolent side-effect of this focus could be to foster greater decentralization: If centralization or vertical integration of different DeFi functions under one person or group carries heavier regulatory burdens, then there is greater incentive to remain decentralized.

Conclusion

Any discussion of “DeFi regulation” must start with a sound understanding of the functions within the DeFi ecosystem, their unique risks and how they are or are not analogous to regulated TradFi activities. It is my hope that this will clear up many misconceptions and get people focused on talking about which regulations make sense for which functions, being as specific and technologically accurate as possible.

[1] “Cast” means broadcast or narrowcast. A broadcast would be a transaction request sent to propagate freely across all nodes in a blockchain network. A narrowcast would be a transaction request sent privately to a particular miner or set of miners. Narrowcast uses include MEV-socialization protocols and ‘white-hat hacking’ social networks where, in order to avoid being “front-run” or to lower their transaction costs, users may wish to have a transaction request made to a miner remain private until it is mined into the blockchain.

firstly, my cut would be convertability ? access? inclusion ? - as regulator or more. where is the action/ control and also support ? that needs regular checking.asovereing i said landmass okay not human body bcos that is destructible er erodable .

as with any structure - ongoing assessment is safest for user/deployer and developer (includes all even packager)

thank you good summation. however, to date - the inaction in landmasses pretending unknown when is deriving benefit makes this neither human / sentient or even ethically responsible . 30 july 2022.

i would assume variance in structure construction and deployment would be indicative of experience to date in work related dynamism . regards. rated? graded? numeric.. weightage i fought and dropped since retail is what creates hackathons also groupisms .community hmm

Is there any role in the Defi ecosystem that *can't* execute it's function in a censorship-resistent manner; pseudonymous, anonymous, jurisdictionally agnostic hosting, etc. Designed to avoid regulatory interference; ungovernable by the State.